|

|

|

[Sponsors] | |||||

They say the only constant in life is change and that’s as true for blogs as anything else. After almost a dozen years blogging here on WordPress.com as Another Fine Mesh, it’s time to move to a new home, the … Continue reading

The post Farewell, Another Fine Mesh. Hello, Cadence CFD Blog. first appeared on Another Fine Mesh.

Welcome to the 500th edition of This Week in CFD on the Another Fine Mesh blog. Over 12 years ago we decided to start blogging to connect with CFDers across teh interwebs. “Out-teach the competition” was the mantra. Almost immediately … Continue reading

The post This Week in CFD first appeared on Another Fine Mesh.

Automated design optimization is a key technology in the pursuit of more efficient engineering design. It supports the design engineer in finding better designs faster. A computerized approach that systematically searches the design space and provides feedback on many more … Continue reading

The post Create Better Designs Faster with Data Analysis for CFD – A Webinar on March 28th first appeared on Another Fine Mesh.

It’s nice to see a healthy set of events in the CFD news this week and I’d be remiss if I didn’t encourage you to register for CadenceCONNECT CFD on 19 April. And I don’t even mention the International Meshing … Continue reading

The post This Week in CFD first appeared on Another Fine Mesh.

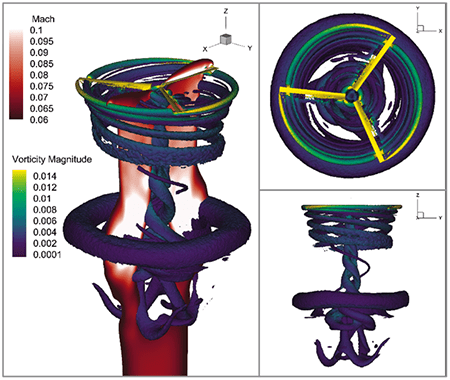

Some very cool applications of CFD (like the one shown here) dominate this week’s CFD news including asteroid impacts, fish, and a mesh of a mesh. For those of you with access, NAFEM’s article 100 Years of CFD is worth … Continue reading

The post This Week in CFD first appeared on Another Fine Mesh.

This week’s aggregation of CFD bookmarks from around the internet clearly exhibits the quote attributed to Mark Twain, “I didn’t have time to write a short letter, so I wrote a long one instead.” Which makes no sense in this … Continue reading

The post This Week in CFD first appeared on Another Fine Mesh.

Severe weather — like thunderstorms, tornadoes, and hurricanes — can push air upward into a higher layer of the atmosphere and trigger gravity waves. Aboard the International Space Station (ISS), the Atmospheric Waves Experiment (AWE) instrument captures these waves by looking for variations in the brightness of Earth’s airglow (above). Recently, when Hurricane Helene hit the southeastern United States, AWE caught a series of gravity waves some 55 miles up, pushed by the storm (below). It’s incredible to see these long-ranging ripples spreading far beyond the heart of the storm. (Video credits: NASA Goddard and Utah State University)

A glowing arch of red, pink, and white anchors this stunning composite astrophotograph. This is a STEVE (Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement) caused by a river of fast-moving ions high in the atmosphere. Above the STEVE’s glow, the skies are red; that’s due either to the STEVE or to the heat-related glow of a Stable Auroral Red (SAR) arc. Find even more beautiful astrophotography at the artist’s website and Instagram. (Image credit: L. Leroux-Géré; via APOD)

Though only 5 cm long, the squirting cucumber can spray its seeds up to 10 meters away. The little fruit does so through a clever combination of preparation and ballistic maneuvers. Ahead of launch, the plant actually moves water from the fruit into the stem; this reorients the cucumber so that its long axis sits close to 45 degrees. It also makes the stem thicker and stiffer.

When the burst happens, fruit spews out a jet of mucus that propels the seeds at up to 20 m/s. The initial seeds move the fastest — thanks to the fruit’s high-pressure reservoir — and fly the furthest. As the pressure drops, the jet slows and the fruit’s rotation sends the seeds higher, causing them to land closer to the original plant. With multiple fruits in different orientations, a single plant can spread its seeds in a fairly even ring around itself. (Research and image credit: F. Box et al.; via Gizmodo)

Just as rivers have tributaries that feed their flow, small glaciers can flow as tributaries into larger ones. This astronaut photo shows Siachen Glacier and four of its tributaries coming together and continuing to flow from the top to the bottom of the image. The dark parallel lines running through the glaciers are moraines, where rocks and debris are carried along by the ice. Those seen here are medial moraines left by the joining of tributaries. When glaciers retreat, moraines are often left behind, strewn with sediment that ranges from the fine powder of glacial flour all the way to enormous boulders. (Image credit: NASA; via NASA Earth Observatory)

In mid-January 2022, the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai (HTHH) volcano had one of the most massive eruptions ever recorded, destroying an island, generating a tsunami, and blanketing Tonga in ash. Volcanologists are accustomed to monitoring nearby seismic equipment for signs of an imminent eruption, but researchers found that the HTHH eruption generated a surface-level seismic wave picked up by detectors 750 kilometers away about 15 minutes before the eruption began. They propose that the seismic wave occurred when the oceanic crust beneath the caldera fractured. That fracture could have allowed seawater and magma to mix above the volcano’s subsurface magma chamber, creating the explosive trigger for the eruption. Their finding suggests that real-time monitoring for these distant signals could provide valuable early warning of future eruptions. (Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory; research credit: T. Horiuchi et al.; via Gizmodo and AGU News)

Striped clouds appear to converge over a mountaintop in this photo, but that’s an illusion. In reality, these clouds are parallel and periodic; it’s only the camera’s wide-angle lens that makes them appear to converge.

Wave clouds like these form when air gets pushed up and over topography, triggering an up-and-down oscillation (known as an internal wave) in the atmosphere. At the peak of the wave, cool moist air condenses water vapor into droplets that form clouds. As the air bobs back down and warms, the clouds evaporate, leaving behind a series of stripes. You can learn more about the physics behind these clouds here and here. (Image credit: Y. Beletsky; via APOD)

|

Hi sakro,

Sadly my experience in this subject is very limited, but here are a few threads that might guide you in the right direction:

Best regards and good luck! Bruno |

<-- this dot is just a general sign for multiplication; both multiplication of scalars and scalar multiplication of vectors can be denoted by it; obviously, if I multiply vectors, I will denote them as vectors (i.e. with an arrow above), everything that doesn't have an arrow above is a scalar

<-- this dot is just a general sign for multiplication; both multiplication of scalars and scalar multiplication of vectors can be denoted by it; obviously, if I multiply vectors, I will denote them as vectors (i.e. with an arrow above), everything that doesn't have an arrow above is a scalar and

and  are tangent and cotangent respectively

are tangent and cotangent respectively is logarithm with the base of 10

is logarithm with the base of 10 is natural logarithm

is natural logarithm ,

,  and

and  are all the same thing

are all the same thing

is called diffusion velocity, see, e.g., general.H line 92

is called diffusion velocity, see, e.g., general.H line 92 is called drift velocity, see, e.g., general.H line 63

is called drift velocity, see, e.g., general.H line 63 is declared in the createFields.H file (see line 57), which is a part of interPhaseChangeFoam, and not the part of driftFluxFoam.

is declared in the createFields.H file (see line 57), which is a part of interPhaseChangeFoam, and not the part of driftFluxFoam.dnf install -y python3-pip m4 flex bison git git-core mercurial cmake cmake-gui openmpi openmpi-devel metis metis-devel metis64 metis64-devel llvm llvm-devel zlib zlib-devel ....

{

echo 'export PATH=/usr/local/cuda/bin:$PATH'

echo 'module load mpi/openmpi-x86_64'

}>> ~/.bashrc

cd ~ mkdir foam && cd foam git clone https://git.code.sf.net/p/foam-extend/foam-extend-4.1 foam-extend-4.1

{

echo '#source ~/foam/foam-extend-4.1/etc/bashrc'

echo "alias fe41='source ~/foam/foam-extend-4.1/etc/bashrc' "

}>> ~/.bashrc

pip install --user PyFoam

cd ~/foam/foam-extend-4.1/etc/ cp prefs.sh-EXAMPLE prefs.sh

# Specify system openmpi # ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ export WM_MPLIB=SYSTEMOPENMPI # System installed CMake export CMAKE_SYSTEM=1 export CMAKE_DIR=/usr/bin/cmake # System installed Python export PYTHON_SYSTEM=1 export PYTHON_DIR=/usr/bin/python # System installed PyFoam export PYFOAM_SYSTEM=1 # System installed ParaView export PARAVIEW_SYSTEM=1 export PARAVIEW_DIR=/usr/bin/paraview # System installed bison export BISON_SYSTEM=1 export BISON_DIR=/usr/bin/bison # System installed flex. FLEX_DIR should point to the directory where # $FLEX_DIR/bin/flex is located export FLEX_SYSTEM=1 export FLEX_DIR=/usr/bin/flex #export FLEX_DIR=/usr # System installed m4 export M4_SYSTEM=1 export M4_DIR=/usr/bin/m4

foam Allwmake.firstInstall -j

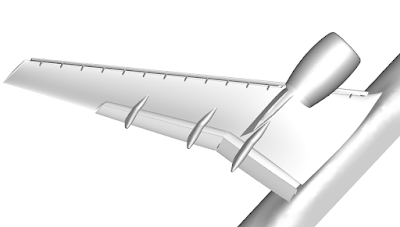

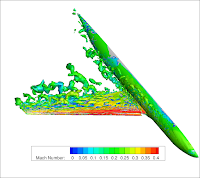

Figure 1: Structured multiblock mesh for a scramjet engine.

1586 words / 8 minutes read

Over half a century has elapsed in designing a working scramjet-powered hypersonic vehicle. Considered harder than rocket engines, designing scramjets is a massive engineering challenge. However, with newer design improvisations such as airframe integration and REST design, scramjet-powered hypersonic flights are close to becoming a reality.

With China and Russia making all the buzz about making successful scramjet-powered hypersonic flights, it looks like the game is on. The West, led by NASA, started the scramjet research in the 1950s. A couple of years into the research, early scientists quickly realized the scientific difficulties of designing scramjets engines. Some say it is harder than rocketry.

This article takes you through the different aspects of scramjet technology, starting with answering the question: what is scramjet, and how is it different from jets and rockets.

What are Scramjets? And how is it different from the Jets and Rockets:

In a jet engine, the flow inside the combustion chamber is subsonic. Even if the jet is flying at supersonic speed, the intake and the compressor slow the air down to low subsonic speed. This increases the pressure and temperature. The higher the flying speed, the higher the rise in pressure and temperatures when we slow the flow down. Normally, in jets, the compressor does the job of raising the pressure and temperature. But if we are moving fast enough, the compressor can be chucked out, and so is the turbine driving it, as just slowing the flow to subsonic conditions will raise the pressure and temperature to the required levels. So, what is left behind without a compressor and turbine is the Ramjet.

A ramjet is a simple tube with an inlet to capture the air and slow it down, a combustor to inject fuel and burn it, and an exhaust nozzle to expand the combustion products to generate thrust. Ramjets can’t start from 0 speed but need about Mach 3 to get going, and they can operate up to Mach 6. Beyond that, the rise in temperature and pressure due to the ram effect is too high for proper combustion.

As a solution, what can be done is the flow can be slowed down just a little bit, thus raising pressure and temperature, but leave it largely supersonic and see if we can do combustion in it. An engine that does just that is the Scramjet – Supersonic Combustion Ramjet. Scramjets that can start operating around Mach 6 can go up to Mach 12 or 14. The upper limit is up for debate as, near the upper Mach limit, we run into the same issue of too much rise in temperature due to slow-down effects to maintain proper combustion. Additionally, near the upper limit, external drag forces become very high, and the heating problems become even more severe.

Rockets, on the other hand, don’t suck air from the atmosphere but carry their own oxygen. Because of this, they are versatile and can fly in any planetary atmosphere and empty space. At the same time, carrying oxygen makes them heavy and less fuel-efficient. So, scramjet is the most attractive option if one wants to fly at hypersonic speeds in Earth’s atmosphere.

Lastly, if one wants to compare these propulsion systems w.r.t fuel efficiency, turbojets are the most fuel-efficient system for the Mach 0 to Mach 3 range. Between Mach 3 and 6, the ramjets are the better performers, while above Mach 6, scramjets are the best. Rockets, even though can operate over all the Mach number regimes, they have the lowest fuel efficiency as they have to carry the oxidizer with them.

The first generation of scramjet engines had a pod-style design with a large axisymmetric spike for external compression. Bearing similarity to gas turbine engines, scramjet pods were designed independently of the vehicle it was meant to propel. In the end, the design was discarded as the supersonic combustion could not overcome the external drag of the spike, as it lacked the much-needed airframe integration.

Hence, from the second generation onwards, the smooth integration of the engine with the vehicle was done. The vehicle is made long and slender for low-drag purposes, and the scramjet engine, with a 2D flow path, is mounted on its belly. The engine is positioned in the shadow of the vehicle’s bow shock to ensure that the vehicle’s forebody does some part of the air compression before entering the engine. In a way, one can say the vehicle is the engine, and the engine is the vehicle in this design.

Unfortunately, even this improved airframe integration design and 2D scramjets had its pitfalls. Ground testing of these geometries revealed that 2D scramjets were not optimum for structural efficiency and overall performance. This led to the development of the current 3rd generation scramjets involving truly 3D geometries. In this design, along with integrating the scramjet into the airframe, the combustors started to have rounded or elliptical shapes.

One example of present-day 3D scramjets is the Rectangular-to-Elliptical Shape Transition or REST scramjet engines. This class of engines has a rectangular capture area that helps smooth integration with the vehicle. The rectangle cross-section gradually transitions into an elliptical cross-section as it reaches the ‘rounded’ combustor.

An elliptical shape for the combustor is preferred over a rectangular shape because it offers a reduced surface area for the same amount of airflow. This aspect of a reduced surface area significantly lowers the engine drag and cooling requirement compared to a rectangle shape. Further, the elliptical shape reduces structural weight due to the inherent strength of rounded structures. Also, the curved shape eliminates low momentum corner flows, which are observed to severely limit engine performance.

The air inside a scramjet engine passes through three distinct processes of compression, combustion, and expansion in the 3 sections: intake, combustor, and exhaust nozzle.

The Intake: The front part of the engine, the intake, does the job of capturing the air and compressing it. At station 0, the flow is undisturbed by the engine. As it moves towards station 1, the air starts to experience compression due to the flow contraction caused by the vehicle’s fore-body. Further compression is done by 3 shock waves generated in the intake. The flow passing through shock waves raises the pressure and temperature of the flow. Each shock wave aligns the flow to the walls of the intake, and by the time the flow leaves the inlet at station 2, it will be uniform and parallel to the walls of the combustor.

The Combustor: At the entrance to the combustor, between stations 2 and 3, a short duct called an isolator exists, which separates the inlet operations from the pressure rise in the combustor. At station 3, the fuel is injected and lighted. It burns in the hot air that has been compressed by the inlet.

The Nozzle: Lastly, the combustion products expand through the exhaust nozzle located between stations 4 and 10. It’s here the thrust for the vehicle gets generated.

Although functioning-wise, a scramjet engine looks simple, designing a working engine that can sustain combustion for an extended period and survive under hypersonic conditions is a daunting challenge. Several engineering difficulties exist, starting with the challenge of mixing the fuel with air and igniting it in a high-velocity flow field within less than 1 millisecond.

The second issue is the high surface heat loads generated by hypersonic flight. These can be greater than those experienced by the space shuttle on re-entry and for longer periods. The material used to build the scramjet structure needs to be lightweight and be able to withstand elevated temperatures in excess of 2000 C. Also, thermal and structural design needs to take care of thermal expansion. Materials grow as they get heated up. So, designing a structure that does not break up as its skin heats up from room temperature to 2000 C is a major engineering challenge.

Thirdly, burning fuel in a duct can sometimes lead to choking or flow blockage. So, some mechanism needs to be built to manage it. Finally, chemical reactions can freeze in the nozzle expansion, leading to incomplete combustion.

Along with these engineering challenges, there are system-level challenges. One of the major issues is scramjets don’t work below Mach 4, so there is a need for another type of propulsion system, say, a ramjet or a rocket engine, to get it up to speed. Lastly, the nature of the scramjet operation changes considerably with the Mach number. Hence, acceleration over a large Mach range will be difficult as needed to get to space.

Given their characteristics of better fuel efficiency and high manoeuvrability, scramjets are preferred over rockets for hypersonic flights in the Earth’s atmosphere. They will likely find applications in hypersonic aeroplanes or cruisers and recoverable space launchers or accelerators. Cruisers could be a vehicle that is boosted to a certain speed by a jet-ramjet combo engine and may spend most of its time at constant velocity in the upper atmosphere. On the other hand, accelerators could probably be a part of a multi-stage rocket-scramjet combo system for low-cost reusable access to space.

Scramjets have come a long way over the last 60 years. 3D scramjet idealogy has proliferated in recent times and is been widely adopted by researchers worldwide. Also, 3D scramjets like REST have opened up the available design space, allowing possibilities for newer design variants to be tested and explored. Hopefully, this will lead to better engines with improved performance and make hypersonic flights a reality in the near future.

1. “Parametric Geometry, Structured Grid Generation, and Initial Design Study for REST-Class Hypersonic Inlets“, Paul G. Ferlemann, et al., JANNAF Airbreathing Propulsion Subcommittee Meeting, La Jolla, California, 2009.

2. “Investigation of REST-class Hypersonic Inlet Designs“, Rowan J. Gollan et al., 17th AIAA International Space Planes and Hypersonic Systems and Technologies Conference, 11-14th April 2011, San Francisco, California.

3. ” “Design of three-dimensional hypersonic inlets with rectangular-to-elliptical shape transition“, Smart, M. K et al., Journal of Propulsion and Power, Vol. 15, No. 3, 1999, pp. 408–416.

4. “Free-jet Testing of a REST Scramjet at Off-Design Conditions“, Michael K Smart et al., Smart, Michael K, et al., 25th AIAA Aerodynamic Measurement Technology and Ground Testing Conference, 5-8 June 2006, San Francisco, California.

5. “Scramjet Inlets“, Professor Michael K. Smart, RTO-EN-AVT-185.

6. “Hypersonic Airbreathing Propulsion“, David M. Van Wie, et al., Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, Volume 26, Number 4 (2005).

7. “Hypersonic Speed Through Scramjet Technology“, Kevin Dirscherl et al., University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder, Colorado 80302, December 17, 2015.

By subscribing, you'll receive every new post in your inbox. Awesome!

The post Hypersonic Flights by Scramjet Engines appeared first on GridPro Blog.

Figure 1: Hexahedral mesh for accurate capturing of leakage gaps in screw compressors.

1106 words / 6 minutes read

Leakage flows stand out as the primary factor leading to decreased efficiency within screw compressors. Precisely capturing these leakage flows using enhanced grids plays a crucial role in achieving precise CFD predictions of their behavior and their consequential impact on the overall performance of the screw compressor.

Rotating volumetric machines like screw compressors or tooth compressors are used extensively in many industrial applications. It is reported that nearly 15 percent of all-electric energy produced is used for powering compressors. Even a small improvement in the efficiency of these rotary compressors will result in a significant reduction in energy consumption. In fact, a small variation in rotor shape hardly visible to the naked eye can cause a notable change in efficiency.

Research indicates that the primary factor leading to efficiency reductions in screw compressors is leakage. This leakage occurs as a result of gaps present between rotors and between rotors and the casing. Among various thermo-fluid behaviours, internal leakage has a more substantial impact, particularly when operating at lower speeds and higher pressure ratios.

With improvement in energy efficiency becoming the main objective of design and development teams, there is a growing interest in flow patterns within screw compressors, particularly focusing on the phenomenon of leakage flows.

Screw compressors operate by altering the volume of the compression chamber, leading to corresponding variations in internal pressure and temperature. As pressure builds up during compression, the compressed gas seeks to move into lower-pressure chambers through the leakage gaps.

Unfortunately, due to the helical nature of the compression process in positive displacement machines, it is very difficult to visually appreciate this leakage flow by any experimental methods. Also, the complex flows in screw compressors demand more detailed studies, which makes conducting physical experimentation very expensive. Hence, experimental studies in these machines have become less attractive, while CFD, with accurate prediction abilities along with detailed 3D flow measurement and visualization capabilities, has been accepted as the workable alternative.

In positive displacement machines, leakage flow is an inescapable devil. Due to the nature of the mating parts and the need for clearances between them, the compressor is bound to have several leakage paths. About 6 different leakage paths have been identified, as shown in Figure 2.

Out of these, only the cusp blow holes have a constant geometry, while the rest of the paths have a geometry and flow resistance that varies periodically in a way unique to each individual path. Further, the pressure difference driving the fluid along a leakage path also varies periodically in a manner that is unique to each leakage path.

Leakages can broadly be categorized into two groups. In the first kind, the leakage happens from the enclosed cavity or discharge chamber to the suction chamber. This causes a reduction in both volumetric and indicated efficiencies. While in the second group, leakage flow occurs from the enclosed cavity or the discharge chamber to the following enclosed cavity. Although the indicated efficiency reduces in this mode, the volumetric efficiency does not.

Each leakage path uniquely influences the performance of the compressor. Hence, it is important to understand the attributes of the leakage through each leakage path and the percentage by which it can impact the machine’s efficiency. This is essential because it helps prioritise the design procedures in general and specifically enhancing the rotor lobe profile.

The critical factor which affects the CFD performance prediction of twin screw compressors is the accuracy with which leakage gaps are captured by gridding strategies. Since the working chamber of a screw machine is transient in nature, we need a grid that could accurately represent the domain deformation.

One approach is simply increasing the grid points on the rotor profile. Studies have shown that grid refinement in the circumferential direction directly influences mass flow rate prediction. In contrast, it has a lesser influence on predicting pressure and power. However, since we want to do a transient simulation in a deforming domain, this gridding approach will cause quicker deterioration in grid quality and a rapid rise in computational time.

Alternatively, another effective way to tackle this discretization challenge is to locally refine only the interlobe space region. This particular area holds utmost significance in managing leakage flows. By confining the increase in cell count to the interlobe gaps and blow-hole areas, the overall grid dimensions can be maintained under control.

The benefits of mesh refinement in the vicinity of interlobe gap and blow-hole area can be seen in improved accuracy in predicting mass flow rate and leakage flows. Interlobe refinement improves the curvature capturing of rotor profiles and also the mesh quality. This is reflected in the CFD predictions.

The difference between experimental indicated power and CFD predictions on the base grid is about 2.7% at 6000 rpm and 6.6% at 8000 rpm. With interlobe grid refinement, the difference reduces to 1.4% at 6000 rpm and 2.8% at 8000 rpm.

The enhancement of the interlobe grid refinement significantly impacts the flow rate. The contrast between experimental outcomes and CFD projections on the base grid is noticeable, registering at 11% and 8.7% for 6000 rpm and 8000 rpm respectively. These disparities decrease notably to approximately 5.5% and 2.9% following grid refinement.

The volumetric efficiency prediction on the base grid is 7% lower than the experiment. With refinement, the difference reduces to 3%. As with other variables, the difference is smaller at 8000 rpm than at 6000 rpm.

Specific indicated power, reliant on indicated power and mass flow rate, displays sensitivity. At 6000 rpm, the difference between the base grid CFD prediction and experimental-specific indicated power is about 0.2 kW/m3/min, which reduces to 0.15 kW/m3/min with refinement. At 8000 rpm, the CFD predictions match with the experiment, as can be seen in Figure 7.

The findings suggest that employing finer grids leads to better capturing of the rotor geometry, thereby enhancing the accuracy of leakage loss representation. With successively refined grids, the reduction in leakage losses becomes apparent. As a result, the CFD predictions gradually align more closely with experimental data.

1. Challenges in Meshing Scroll Compressors

2. Automation of Hexahedral Meshing for Scroll Compressors

3. The Art and Science of Meshing Turbine Blades

1.“The Analysis of Leakage in a Twin Screw Compressor and its Application to Performance Improvement”, John Fleming et al., Proc Instn Mcch Engrs Vol 209, 1995.

2. “Analytical Grid Generation for accurate representation of clearances in CFD for Screw Machines”, S Rane et al., Article in British Food Journal · August 2015.

3. “Grid Generation and CFD Analysis of Variable Geometry Screw Machines”, Sham Ramchandra Rane, PhD Thesis, City University London School of Mathematics, Computer Science and Engineering August 2015.

4. “ CFD Simulations of Single- and Twin-Screw Machines with OpenFOAM”, Nicola Casari et al., Designs 2020.

5. “Numerical Modelling and Experimental Validation of Twin-Screw Expanders” Kisorthman Vimalakanthan et al., Energies 2020, 13, 4700.

6. “New insights in twin screw expander performance for small scale ORC systems from 3D CFD Analysis”, Iva Papes et al., Journal of Applied Thermal Engineering, July 15, 2015.

7. “A GRID GENERATOR FOR FLOW CALCULATIONS IN ROTARY VOLUMETRIC COMPRESSORS”, John Vande Voorde et al., European Congress on Computational Methods in Applied Sciences and Engineering, ECCOMAS 2004.

8. “CFD SIMULATION OF A TWIN SCREW EXPANDER INCLUDING LEAKAGE FLOWS”, Rainer ANDRES et al., 23rd International Compressor Engineering Conference at Purdue, July 11-14, 2016.

9. “Calculation of clearances in twin screw compressors”, Ermin Husak et al., International Conference on Compressors and their Systems 2019.

By subscribing, you'll receive every new post in your inbox. Awesome!

The post Accurate Capturing of Leakage Gaps in Screw Compressors with Hex Grids appeared first on GridPro Blog.

Figure 1: Automated gerotor pump meshing with GridPro’s structured multiblock grid generator.

1454 words / 7 minutes read

Automated hexahedral mesher empowers engineers to effortlessly scrutinize the flow behaviour, vividly understand the change in flow with the change in clearance gap, and explicitly bring out the differences in the gerotor design variant’s performances.

The unique characteristics of gerotor pumps have made them a widely used pumping device in various industries. They are compact, reliable, and inexpensive, making them a cost-effective option for fluid transfer applications. Additionally, they offer high tolerance to fluid contamination, aeration, and cavitation. By providing excellent flow control, minimal flow pulsation and low noise, they have a strong footprint in the aerospace, automotive and manufacturing sectors.

The aerospace industry uses them for cooling, lubrication, and fuel boost and transfer processes. In manufacturing, they are used for dosing, filling, dispensing, and coating applications. Gerotor pumps are also extensively used in the automotive, agriculture, and construction fields, particularly for low-pressure applications. With the progress of technology, gerotor pumps are finding new applications in the life science, industrial, and mechanical engineering sectors.

This expansion in applicability across various industries is driving the gerotor pump research for further improvement. Also, the growing environmental concern in various industries is creating a need for newer applications, which demand pumps that can improve their efficiency. Gerotor pumps, with their simple design, have presented themselves as an attractive option for these newer applications. However, the increasing demand for pumps that meet stringent specifications and shorter design cycles necessitates a cost-effective design process that can lead to optimal performance and efficiency.

This has driven further research on gerotor pumps, focusing on improving design through numerical simulation, allowing designers to identify potential performance issues and optimize their designs before building physical prototypes. By leveraging this approach, researchers are leading the way towards more efficient and reliable gerotor pump designs that meet the growing demand for pump applications in various industries.

CFD is an essential tool for the design and optimization of gerotor pumps. CFD simulations accurately predict the effect of cavitation and fluid-body interaction on performance by providing a detailed description of the fluid’s behaviour inside the pump. Due to its accuracy, CFD is often used as a benchmark for pump experiments when no experimental comparison data is available.

However, there are certain challenges in using CFD for gerotor pump design. The CFD process requires large simulation time and memory requirements, and there is a need to re-mesh the entire domain at each angular step. Further, meshing the inter-teeth clearance and constantly changing fluid domain could be a challenging task.

These constraints can delay the design verification stage, making the process time-consuming. The design engineer must mesh the volume chambers each time the design changes and perform a time-consuming simulation. In most cases, the simulation of a geometric configuration takes up to a day to generate results. This workflow hinders the effectiveness of rapid design methodologies or the easy testing of a large number of geometric configurations of the pump in a reasonable time.

The primary focus of research w.r.t meshing positive displacement machines is the development of methodologies to support rapid simulation of any geometry. Efforts are made to develop meshing methods to automatically generate high-resolution grids with optimal cell size and high quality without human intervention.

However, gerotor pump meshing is challenging due to the rotating and deforming fluid volumes created during their working cycle. The rapid transformation of the deforming fluid zone from a large pocket region to a narrow passage makes meshing extremely difficult, w.r.t maintaining cell resolution, cell quality and mesh size. Trying to attain one of these meshing objectives results in the failure of the other. On top of this, coming up with a meshing procedure to avoid human intervention further ups the difficulty levels.

Additionally, the tight clearance space, which plays a significant role in determining volumetric efficiency, presents another obstacle for CFD simulations. These clearances are extremely small, often in the range of a few microns, and impact various aspects of the pump’s performance, such as flow leakage, flow ripple, cavitation, pressure lock, torque, and power. Out of these, the flow ripple parameter is significantly affected by the design of the tip and side gaps. A high ripple in the outlet flow can cause high levels of vibration and noise in the pump.

Hence it is critically important to accurately represent these narrow gaps with high-resolution, high-quality meshes to bring out their effects in high clarity. Low-resolution coarse grids will decrease the accuracy and may lead to over or underestimation of the flow variables. Maintaining a certain mesh quality is also important, as it enables CFD to easily analyse variations in clearances and other tendencies.

Various meshing techniques have been employed over time to discretize the gerotor fluid space. Among them, overlapping meshing methods, deform and remesh methods and customised structured meshing are the most popular ones.

Overlapping meshing methods, including the overset and immersed boundary methods, are frequently used. Although they are quick to generate, they often fall short of properly resolving the boundary layer and narrow clearance gaps while also employing an excessive number of cells.

The deform and remesh method is another popular approach that offers automation but often generates grids with a large cell count. Unfortunately, these methods can cause interpolation errors and stability issues while running the CFD solvers.

While manual customised grid generation methods provide the best mesh in terms of cell quality and grid size, they demand excessive time and human effort to generate the mesh. Unlike the generic moving mesh methods, such as the immersed boundary method, manual gridding approaches, such as the structured moving/sliding methods, accurately represent the dynamic gaps.

In the structured moving/sliding mesh approach, the fluid volume of the rotor chamber is isolated from the stationary fluid volumes related to the suction and delivery port. The rotor volume is topologically similar to a ring, making it easy to create an initial structured mesh for this shape. This zone being an extrudable domain, a 2D grid is created, which is later extruded to get a 3D mesh.

The stationary fluid volumes of the suction and delivery port are meshed using unstructured approaches. They are linked to the rotor mesh volume via non-conformal interfaces.

When the inner gear surface shifts to a new position, the mesh on the surface does not simply move with it. Instead, the mesh “slides” on the inner gear surface while adjusting to conform to the new clearance between the inner and outer gear surfaces. Simultaneously, the interface connections between the rotor volume and other fluid volumes are updated. These meshing steps ensure good resolution of the clearance space while maintaining good cell quality.

GridPro addresses the gerotor pump meshing challenge with its unique single-topology multi-configuration approach. To start with, for a given instance of the inner and the outer gear position, a 2D wireframe topology is built. Since the meshing zone is 2.5D in nature, a grid in 2D is good enough, which is later extruded in the perpendicular direction to get the 3D grid. The 2D topology acts as a template, to be later used repeatedly to generate mesh for all instances of the inner and outer gear positioning.

An automated python script ensures the grids for all angular steps are generated in an automated, hands-free environment. The script rotates the inner and outer gear at a user-specified angular step of 0.1 degrees and gives out a grid with consistent mesh quality. Since the topology is the same, the mesh generated for each angular step is practically the same. This particular aspect brings in significant positive benefits when compared to an unstructured re-meshing approach where the cell count and connectivity are completely different from one angular step grid to another.

This consistency in grids generated for all instances of the gear position aids in generating superior flow field simulation results. The automated meshing environment saves time and human effort and provides the much-needed trust of the design engineer in the simulated CFD data.

Engineers can enhance their workflow for 3D CFD analyses of gerotor pumps with an automated hexahedral mesher. It will empower engineers to effortlessly scrutinize the flow behaviour inside the working chambers, vividly understand the change in flow physics with variation in clearance gap, and explicitly bring out the differences in parametric design variant’s performances.

More importantly, an automated mesher brings the engineers’ focus back to the design aspects of the pump rather than on the meshing.

By subscribing, you'll receive every new post in your inbox. Awesome!

The post Automated Hexahedral Meshing of Gerotor Pumps appeared first on GridPro Blog.

Figure 1: Block Adapted Shock Fitted Structured Grid for Hypersonic Simulations for Orion Reentry Capsule Configuration.

1483 words / 7 minutes read

Discover the advancements in flow feature-aligned structured grid generation for hypersonic simulations with strong shocks. This article explores the innovative shock-fitting feature in GridPro, which aligns mesh blocks with shock contours to improve accuracy and reduce computational costs. Learn how this new technique outperforms traditional methods by simplifying grid alignment and enhancing shock capture, making it ideal for complex geometries with multiple shocks.

Computational fluid dynamics is critically essential and highly recommended for predicting the aerothermal environment of reentry vehicles experiencing hypersonic flow. In these regimes, shock waves are a dominant flow phenomenon. It is needless to say capturing these shock waves to the finest level possible is critically essential for accurately predicting the hypersonic flow field. Traditionally, two distinct approaches, known as shock fitting and shock capturing, have been widely used to handle such discontinuities.

Shock Capturing involves implicit handling of shocks through numerical schemes that can deal with discontinuities without explicitly locating them. They employ artificial viscosity or flux limiters to stabilize the solution and prevent non-physical oscillations. However, they may produce smeared shock profiles and require fine grids to achieve higher accuracy, potentially increasing computational costs.

Shock Fitting, on the other hand, explicitly tracks the position of shock waves within the CFD domain. It treats the shock as a moving boundary within the domain, solving additional equations to update its position and speed. This approach provides a sharp and accurate representation of shocks without the smearing effects seen in shock capturing. However, it is more complex to implement, requiring additional equations for shock dynamics and frequent grid adjustments to accommodate moving shocks.

To sum up, shock capturing is robust, versatile and easier to apply to a wide range of problems, albeit with potential accuracy trade-offs. while on the other hand, shock fitting offers superior accuracy for specific applications but at the cost of increased complexity and implementation effort.

To tackle the challenge of accurately representing shock features, engineers at GridPro have developed a new feature, which enables shock-fitted structured grid generation by aligning grid blocks with the shock contour. This article provides an in-depth discussion of this novel method.

The computational fluid dynamics workflow begins with the creation of a base structured multi-block mesh for the desired geometry and conducting an initial CFD simulation using this mesh. Following this, post-processing is carried out to extract an iso-contour Mach sheet that passes through the shock.

This Mach iso-contour surface serves as a reference to realign the mesh blocks. By adjusting the topology to align the blocks with the shock, a new mesh is generated with cells more effectively positioned to capture the thin, three-dimensional shock. This updated grid is then used for a second simulation, and the process is repeated until the user achieves the desired level of accuracy in the results.

To commence the simulation, an initial structured grid must be created. The baseline mesh adopts an analytical sphere as its outer domain, with no specialized adjustments made to accommodate shock features. This streamlined approach allows for swift setup of the initial grid, requiring minimal effort and time investment. Furthermore, maintaining symmetry along the X-Y plane aids in reducing grid points, thereby enhancing simulation efficiency.

Following the structured grid generation, the flow simulation is conducted using MISTRAL, a Navier-Stokes solver tailored for reacting flows.

Initially, the solution is computed on an Euler grid, without implementing specialized boundary layer clustering for the capsule wall.

This simplification is deliberate, aimed at minimizing computational time, as the primary focus of the initial iteration is the extraction of the shock surface.

The process of detecting and extracting shocks commences with the post-processing of the MISTRAL solution to derive the Mach distribution in the flow domain. The location of the bow shock is determined by selecting a percentage of the freestream Mach number, typically ranging between 90% to 95%. Subsequently, a Mach iso-contour sheet is extracted from the flow solution utilizing the Paraview visualization package. Following the extraction, the Mach sheet is saved as an STL file and imported into GridPro for further processing.

Given the coarse resolution of the bow shock on the initial grid, the Mach iso-surface may display roughness. To address this, a smoothing process becomes imperative. Utilizing GridPro’s built-in subdivision scheme, the extracted Mach contour is smoothed and enhanced to make it more suitable for subsequent stages of the shock-capturing procedure.

With the shock contour sheet in hand, we’re ready to delve into the actual shock-capturing process. Firstly, the tool automatically pinpoints the block faces closest to the extracted shock contour sheet. Next, those faces proximate to the shock undergo splitting and a buffer layer of the block is created around the shock. Notably, this splitting operation maintains the integrity of the block structure, relieving the user from the burden of resolving any ensuing issues.

Following this, blocks lying beyond the buffer layer are automatically deleted (as shown in Figure 7a). Next, a new outer domain surface, encapsulating the capsule is generated by scaling up the shock contour sheet by a small percentage.

Consequently, the outer faces of the buffer layer blocks serve as the boundary faces of this new outer envelope, establishing a zone characterized by shock-aligned grid lines. A detailed view of the mesh obtained after the initial shock-fitting iteration is presented in Figure 7b.

It’s important to note that the decision to split the topology hinges on the specifics of each case. In scenarios where there’s no need to reduce the computational domain’s size, this step may be bypassed. However, in instances like the one described here, where pinpointing the shock’s location and the primary flow physics region is challenging before simulation, employing this process can significantly slash the computational domain by over half. Such reduction translates into substantial savings in computational time and resources.

The Mach contour image in Figure 8 clearly demonstrates that the shock is significantly crisper and closer to the body. The cells are noticeably better aligned with both the general flow direction and the shock’s location. Remarkably, just one shock-fitting iteration was sufficient to achieve a good solution, highlighting the efficiency and effectiveness of the block-adapted shock alignment method.

The computed results are compared to data from Reference, which utilizes the US3D code. Figure 9 compares surface pressure variation along the symmetry line (in the z direction) of the capsule. The maximum pressure error is less than 1%, which is well within acceptable standards, validating the quality of the obtained solution.

The next test case considered to validate the tool was the leading nose region of the Space Launch System. Two structured grids were generated- a baseline grid (0.7 million) and a shock-fitted grid (0.762 million) and CFD computations were done at Mach 5. Figure 10 shows the grids and the improvement in the flow field with the block-adapted shock alignment method.

The third test case involves hypersonic simulations for a blunt body configuration at Mach 20. Here also 2 grids – Baseline (5.92 million) and shock-fitted grids (5.61 million) were employed. Figure 11 below shows the crisp representation of the bow shock with block-adapted shock-fitted grids.

The block-adapted shock alignment approach is straightforward to implement, requiring fewer re-meshing and CFD simulation iterations compared to other shock-fitting procedures or adaptive shock-capturing methods. Additionally, it only increases the cell count of the base grid by a smaller amount.

This method can be seamlessly integrated into the existing GridPro-CFD solver-post-processor loop without any modifications. The base-structured hexahedral meshes, with their inherently low dissipation properties, enhance shock capture accuracy. By using the shock surface to identify shock-interfering blocks and refining these blocks through wrapping, the resulting grid is sufficiently dense and aligned with the shock contour to capture it accurately. Typically, executing this loop for one or two iterations is sufficient.

A key advantage of this approach is the minimal increase in cell count and the presence of one-to-one connected cells. Due to the limited number of iterative loops and uni-directional cell refinement, the increase in cell count remains marginal. Importantly, any computational fluid dynamics solver compatible with hexahedral meshes can utilize the shock-fitted grids, as one-to-one cell connectivity with neighbouring cells is consistently maintained.

A workflow for shock-fitting grid generation has been developed and rigorously tested, proving effective in accurately capturing shocks. Demonstrated through the Orion re-entry capsule and SLS rocket test cases, this new mesh generation process can rapidly produce accurate CFD estimates for hypersonic geometries. It stands as a viable and promising alternative to traditional shock-fitting or shock-capturing mesh generation methods. The efficacy of these novel approaches is evident, showcasing significant improvements in the flow field due to the highly precise representation of the shock contour.

By subscribing, you'll receive every new post in your inbox. Awesome!

The post Fast and Accurate Hypersonic CFD Simulations: Impact of Automatic Shock-Aligned Meshes appeared first on GridPro Blog.

Figure 1: GridPro Version 9 Feature Image.

1532 words / 7 minutes read

In the ever-evolving landscape of grid generation, the goal of having an autonomous and reliable CFD simulation is the driving force behind progress. We’re thrilled to announce the release of GridPro Version 9, a major update that brings many new features, improvements, and powerful tools to empower users to achieve this vision. This release marks a significant milestone in our commitment to automate structured meshing. We have two new verticals released along with GridPro Version 9:

This article presents a few highlights. To learn more about other features packed in Version 9, Check out the release notes and What’s New.

To align ourselves with CFD_Vision_2030_Roadmap, we now use ESP as our modelling environment. With the introduction of this new environment, we aim to provide an adequate linkage between GridPro and the upfront CAD system. We have implemented a host of CAD creation tools, which enables users to create basic geometries in GridPro using the CAD panel.

As the first linking step in any Upfront CAD package, GridPro can import the labelling and grouping from any CAD package upstream through our improved STEP file format. The labels created in CAD software can be edited or inherited as surface and boundary labels in the mesh exported from GridPro, creating a seamless integration with the solver downstream.

In GridPro Version 9, labelling/grouping can also be used to split the underlying surface mesh. In the previous version, surfaces were split to improve the volume mesh quality based on the feature angles, but now users can also split surfaces by utilizing surface labels/groups. This saves time and reduces the manual effort required to select multiple surfaces for splitting purposes.

One of the significant challenges with traditional structured meshing is to dynamically update 3D blocking in the design and analysis of many engineering applications. Especially in scenarios involving shape optimization, moving boundary problems, etc. This requires the user to regenerate the blocks for every design change. It is a tedious and very time-consuming task to recreate a block structure after every design iteration.

GridPro, being a topology-based mesher, could readily accommodate geometry variations without any additional changes to the blocking. However, when geometries have non-uniform scaling, the parts of the block topology have to be moved close to the geometry to be mapped. This could become a time-consuming process, but with the introduction of the Block Mapping tool, the mapping can be done with a few clicks.

GridPro’s flexible topology paradigm enables users to create blocks without any restrictions. This sometimes results in the user creating poorly shaped blocks. Though the mesh generation engine smooths the poorly shaped blocks, it increases the mesh convergence time. With the new topology, smoother, irregularly placed blocking is now repositioned to provide a better intuition and speed up the meshing time. With this new feature, the time for grid generation is significantly reduced by an order of magnitude in many cases.

To improve hypersonic simulation workflows, GridPro introduces a Shock Alignment feature. This innovation adapts the grid blocks to the shock formed in a baseline solution. By splitting blocks in the shock region and aligning the grid normal to the shock surface, the algorithm enhances simulation accuracy and accelerates convergence. This advancement allows users to achieve faster and more precise results, optimizing their computational fluid dynamics analyses. With GridPro’s Shock Alignment, engineers and researchers can tackle complex hypersonic flows more efficiently and reliably. (Check out the paper published in the AIAA Hypersonics Conference: A Shock Fitting Technique For Hypersonic Flows Using Hexahedral Meshes.)

In GridPro, we have combined the benefits of unstructured meshing like local refinement, mesh adaptation, and multi-scale meshing by adapting the multi-block structure. This is done with a feature called Nesting, In this version we have released another flavour of nesting called the clamped nest. Clamped nesting aggressively refines the mesh near the geometry while coarsening it outside the region. This technique is particularly effective in creating highly refined regions, especially for LES and DNS simulations.

To speed up the block creation time for repeated geometries, an Array-block replication option is introduced. This provides the capability to replicate a topology in multiple directions. This tool is particularly advantageous when dealing with similar geometric patterns or shapes. Instead of creating the topology individually for each pattern, users can generate one pattern and seamlessly replicate it across self-similar geometric patterns in three different directions. Utilizing the Array feature, users can create blocking for a single periodic section and extend it in the X, Y, and Z directions.

Starting now, the UI enables the creation of higher-order meshes with ease. Users can choose their preferred higher-order format – quadratic, cubic, or quartic – and the tool will automatically adjust the density to the nearest multiple of the selected order for seamless mesh generation.

Users can also import internally or externally generated higher-order grids into the UI for visualization and quality assessment. The meshes can be observed in various modes, including Only Edges, Edges with Corners, Edges with Nodes, and Edges with All Nodes, allowing for a comprehensive examination.

Moreover, users can evaluate mesh quality parameters such as the Jacobian of the higher-order elements and compare them to the native linear mesh for detailed analysis.

The local block smoothing feature introduced in GridPro Version 9 provides the user a way to eliminate negative volumes ( folds) in the generated mesh locally. The local smoothing is a post-processing step which can be done in the grid to either improve the grid locally or to eliminate negative volumes.

The smoothing feature offers two schemes: Transfinite Interpolation (TFI) and Partial Differential Equation (PDE) smoothing. TFI-based smoothing is computationally less intensive, while PDE-based smoothing, despite its higher computational cost, proves more effective in areas with high curvature, producing meshes with fewer folds.

In version 9, we provide GUI options to harness the control features in the Grid Schedule function. These are designed to accelerate mesh smoothing by leveraging the multi-grid capabilities of structured meshes. Particularly beneficial for large topologies, the approach involves initially running the topology at a lower density. Once the corners are approximately smoothed and positioned, the smoother can be executed for higher densities, contributing to accelerated grid convergence.

Users can insert additional steps to further customize the smoothing process, effectively breaking down the process into multiple stages. After each step, the smoothing computations automatically resume from the previous state, ensuring a seamless and efficient progression.

Now, users can generate multiple Cut Planes, allowing them to create sectional views at various locations and directions. The Cut Plane, employed to clip a portion of a surface or grid, facilitates the examination of its interior, mainly when the area to be meshed is situated inside the surfaces. The enhanced feature of utilizing more than one Cut Plane significantly simplifies the assessment of topology and mesh in complex areas.

In version 9, we introduced the CAD and Meshing API with Python 3 support, empowering users to automate the meshing workflow with greater control. The updated API provides a comprehensive set of commands, including preprocessing and postprocessing operations. Repetitive tasks and batch operations can also be automated. This significantly reduces the user’s time spent on meshing and enhances productivity, particularly for new designs that follow similar workflows.

The new APIs can be tightly integrated with any CAD or optimization system, making them an excellent tool for automating topologically similar geometries. By leveraging the API, users can streamline their design process, ensuring efficient and consistent high-quality meshes and CFD results across different designs.

Upgrading to GridPro Version 9 ! Existing users can easily upgrade to the latest version, while new users can explore the enhanced capabilities by downloading the software from https://www.gridpro.com.

Visit our official website gridpro.com to download the latest version of GridPro!

To see these features in action, visit our Youtube Channel: GridPro Version 9 New Features Playlist.

As we continue to evolve and innovate, GridPro Version 9 reflects our commitment to providing you with the best tools and features to ease the workflow of mesh generation and accuracy of your CFD simulations. We believe these new features and tools will increase reliability and change how you mesh.

By subscribing, you'll receive every new post in your inbox. Awesome!

The post GridPro Version 9 Release Highlights! appeared first on GridPro Blog.

Figure 1: Turbine blade with winglet tips. Image source – Ref [1].

702 words / 3 minutes read

Winglet Tips are effective design modifications to minimize tip leakage flow and thermal loads in turbine blades. A reduction in leakage losses of up to 35-45 % has been reported.

The design and optimization of gas turbines is a crucial aspect of the energy industry. One aspect that has gained significant attention in recent years is the issue of tip leakage flow in gas turbines. Tip clearances, which are provided between the turbine blade tip and the stationary casing, allow free rotation of the blade and also accommodate mechanical and thermal expansions.

However, this narrow space becomes instrumental in the leakage of hot gases when the pressure difference between the pressure side and the suction side of the flow builds up. This is undesirable as it reduces the turbine efficiency and work output. According to some studies, tip leakage loss could account for one-third of the total aerodynamic loss in turbine rotors. Further, leakage flows bring in extra heat, which raises the blade tip metal temperature, thereby increasing the tip thermal load.

It is, therefore, essential to cool the blade tip and seal the leakage flow. Over the years, various design features have been proposed as a solution. One of the promising features employed in tip design is the use of winglets.

Winglet tips comprise of a blade tip with a central cavity and an outward extension of the cavity rim called the winglet. Different variants are developed based on the outward extent of the winglet, the length of the winglet and the location of the winglet. Figure 3 shows three winglet variants derived from the base geometry of the tip with a cavity. The first two have winglets on the suction side with different lengths, while the third one has a small winglet on the suction side as well as on the pressure side.

The flow pattern within the cavity of the winglet-cavity tip is similar to that in the cavity tip. On the blade pressure surface, the flow accelerates toward the trailing edge. On the blade suction surface, the flow accelerates till 60 percent of the tip chord and then decelerates toward the trailing edge. Near the leading edge of the blade tip, the flow enters the tip gap and impinges on the cavity floor of the tip, enhancing the local heat transfer. Then, a vortex forms along the suction side squealer. The vortex within the cavity is called a “cavity vortex.” It is also observed that the flow separates at the pressure-side tip edge, and most of the fluid exits the tip gap straight after entering the tip gap from the pressure-side inlet. Nevertheless, some fluid entering the tip gap mixes with the cavity vortex first and then exits the tip gap. The tip leakage flow exiting the gap rolls up to form a tip leakage vortex.

While generating meshes for leakage flow simulations, having a fine mesh in the leakage gap is critical. The narrow gap should be finely resolved with at least 40-50 layers of cells. In the tangential direction across the tip gap, 30 – 40 layers of cells are required to capture the winglet width and 150-160 cell layers to capture the tip gap from the suction side to the pressure side. Such a fine-resolution structured mesh will lead to a total cell count of about 7 to 9 million.

The boundary layer should be fully resolved with an estimated Y+ less than 1, using a slow cell growth rate of 1.1 to 1.2. Grid refinement studies with grids varying from 6 to 10 million have shown to decrease the tip average heat transfer coefficient by about 1.8 to 1.9% with every 2 million increase in cell count.

The average tip heat transfer coefficient (HTC) and total tip head load increase with an increase in tip gap. HTC is observed to be high on the pressure side winglet due to flow separation reattachment and also high on the side surface of the suction side winglet due to impingement of the tip leakage vortex.

Tip winglets are found to decrease tip leakage losses. Because of the long distance between the two squealer rims, the flow mixing inside the cavity is enhanced, and the size of the separation bubble at the top of the suction side squealer is increased, effectively reducing leakage loss. In a low-speed turbine, the winglet cavity tip is observed to reduce loss by 35-45% compared to a flat tip. When it comes to thermal performance, the tip gap size becomes a major influencing factor.

1. “Heat Transfer of Winglet Tips in a Transonic Turbine Cascade”, Fangpan Zhong et al., Article in Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power · September 2016.

2. “Tip gap size effects on thermal performance of cavity-winglet tips in transonic turbine cascade with endwall motion”, Fangpan Zhong et al., J. Glob. Power Propuls. Soc. | 2017, 1: 41–54.

3. “Turbine Blade Tip External Cooling Technologies”, Song Xue et al., Aerospace 2018, 5, 90.

4. “Aero-Thermal Performance of Transonic High-Pressure Turbine Blade Tips“, Devin Owen O’Dowd, St John’s College, PhD Thesis, Department of Engineering Science, University of Oxford, 2010.

By subscribing, you'll receive every new post in your inbox. Awesome!

The post Cooling the Hot Turbine Blade with Winglet Tips appeared first on GridPro Blog.

We used 3DFoil to perform aerodynamic simulations for a rectangular wing based on a NACA 0012 airfoil. Results were compared with a NACA experiment performed in 1938, Ref. [1]. NACA tested a full sized wing with a span dimension of 36 feet and chord of 6 feet. The tests were performed in a full scale wind tunnel. We compared the results of 3DFoil, our vortex lattice package, against the experiments conducted on the NACA 0012 version of the wing. The results show excellent agreement between 3DFoil and the experiments for the lift and drag coefficients.

References:

Goett, H. J., & Bullivant, W. K. (1938). Tests of NACA 0009, 0012, and 0018 airfoils in the full-scale tunnel. Washington, DC, USA: US Government Printing Office.

3DFoil empowers engineers, designers and students alike to design and analyze 3D wings, hydrofoils, and more. The software seamlessly blends speed and accuracy, using a vortex lattice method and boundary layer solver to calculate lift, drag, moments, and even stability. Its user-friendly interface allows for flexible design with taper, twist, and sweep, making it ideal for creating winglets, kite hydrofoils, and various other aerodynamic surfaces. Notably, 3DFoil surpasses traditional 2D analysis by considering finite wing span for more realistic performance predictions, helping users optimize their designs with confidence.

See also: https://www.hanleyinnovations.com/3dwingaerodynamics.html

Visit 👉 Hanley Innovations for more information

Start the design process now with Stallion 3D. It is a complete computational fluid dynamics, CFD, tool based on RANS that quickly and accurately simulate complex designs. Simply enter your CAD, in the STL format form OpenVSP or other tools, to discover the full potential of your design.

Learn more 👉 https://www.hanleyinnovations.com/stallion3d.html

Stallion 3D is a tool designed for you, the designer, to successfully fly your designs on schedule:

Stallion 3D empowers you to take your designs to the next level. The picture above shows the aerodynamics of an amphibious Lockheed C-130 concept. A Windows 11 laptop was used for the complete calculation. Stallion 3D is ideal for down selecting conceptual designs so you can move to the next step with an optimized aircraft.

Do not hesitate to contact us at hanley@hanleyinnovations.com if you have any questions. Thanks 😀

VisualFoil Plus is a version of VisualFoil that has a built-in compressible flow solver for transonic and supersonic airfoil analysis. As VisualFoil Plus is currently not in active development, the perpetual license is only $189.

Learn more 👉 https://www.hanleyinnovations.com/air_16.html

VisualFoil Plus has the following features:

The picture above, shows referrals the solution of the NACA 0012 airfoil at a Mach number of 0.825.

Please visit us at https://www.hanleyinnovations.com/air_16.html for more information.

When choosing a CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) software for beginners, it's essential to consider factors that balance ease of use with computational power. Here are some key qualities to look for:

1. User-Friendly Interface:

Popular Aerodynamics software Software Options for Beginners offered by Hanley Innovations are:

By considering these factors, you can start to work on your aerodynamics and make significant progress in a short period of time.

Here are instructions on how to import a surface CSV file from Stallion 3D into ParaView using the Point Dataset Interpolator:*

In Stallion 3D

Open ParaView.

Convert CSV to points:

Load the target surface mesh:

Apply Point Dataset Interpolator:

5. Visualize:

Take flight with your next project! Hanley Innovations offers powerful software solutions for airfoil design, wing analysis, and CFD simulations.

Here's what's taking off:

Hanley Innovations: Empowering engineers, students, and enthusiasts to turn aerodynamic dreams into reality.

Ready to soar? Visit www.hanleyinnovations.com and take your designs to new heights.

Stay tuned for more updates!

#airfoil #cfd #wingdesign #aerodynamics #iAerodynamics

In the computation of turbulent flow, there are three main approaches: Reynolds averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS), large eddy simulation (LES), and direct numerical simulation (DNS). LES and DNS belong to the scale-resolving methods, in which some turbulent scales (or eddies) are resolved rather than modeled. In contrast to LES, all turbulent scales are modeled in RANS.

Another scale-resolving method is the hybrid RANS/LES approach, in which the boundary layer is computed with a RANS approach while some turbulent scales outside the boundary layer are resolved, as shown in Figure 1. In this figure, the red arrows denote resolved turbulent eddies and their relative size.

Depending on whether near-wall eddies are resolved or modeled, LES can be further divided into two types: wall-resolved LES (WRLES) and wall-modeled LES (WMLES). To resolve the near-wall eddies, the mesh needs to have enough resolution in both the wall-normal (y+ ~ 1) and wall-parallel directions (x+ and z+ ~ 10-50) in terms of the wall viscous scale as shown in Figure 1. For high-Reyolds number flows, the cost of resolving these near-wall eddies can be prohibitively high because of their small size.

In WMLES, the eddies in the outer part of the boundary layer are resolved while the near-wall eddies are modeled as shown in Figure 1. The near-wall mesh size in both the wall-normal and wall-parallel directions is on the order of a fraction of the boundary layer thickness. Wall-model data in the form of velocity, density, and viscosity are obtained from the eddy-resolved region of the boundary layer and used to compute the wall shear stress. The shear stress is then used as a boundary condition to update the flow variables.

During the past summer, AIAA successfully organized the 4th High Lift Prediction Workshop (HLPW-4) concurrently with the 3rd Geometry and Mesh Generation Workshop (GMGW-3), and the results are documented on a NASA website. For the first time in the workshop's history, scale-resolving approaches have been included in addition to the Reynolds Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) approach. Such approaches were covered by three Technology Focus Groups (TFGs): High Order Discretization, Hybrid RANS/LES, Wall-Modeled LES (WMLES) and Lattice-Boltzmann.

The benchmark problem is the well-known NASA high-lift Common Research Model (CRM-HL), which is shown in the following figure. It contains many difficult-to-mesh features such as narrow gaps and slat brackets. The Reynolds number based on the mean aerodynamic chord (MAC) is 5.49 million, which makes wall-resolved LES (WRLES) prohibitively expensive.

|

| The geometry of the high lift Common Research Model |

University of Kansas (KU) participated in two TFGs: High Order Discretization and WMLES. We learned a lot during the productive discussions in both TFGs. Our workshop results demonstrated the potential of high-order LES in reducing the number of degrees of freedom (DOFs) but also contained some inconsistency in the surface oil-flow prediction. After the workshop, we continued to refine the WMLES methodology. With the addition of an explicit subgrid-scale (SGS) model, the wall-adapting local eddy-viscosity (WALE) model, and the use of an isotropic tetrahedral mesh produced by the Barcelona Supercomputing Center, we obtained very good results in comparison to the experimental data.

At the angle of attack of 19.57 degrees (free-air), the computed surface oil flows agree well with the experiment with a 4th-order method using a mesh of 2 million isotropic tetrahedral elements (for a total of 42 million DOFs/equation), as shown in the following figures. The pizza-slice-like separations and the critical points on the engine nacelle are captured well. Almost all computations produced a separation bubble on top of the nacelle, which was not observed in the experiment. This difference may be caused by a wire near the tip of the nacelle used to trip the flow in the experiment. The computed lift coefficient is within 2.5% of the experimental value. A movie is shown here.

|

| Comparison of surface oil flows between computation and experiment |

|

| Comparison of surface oil flows between computation and experiment |

Multiple international workshops on high-order CFD methods (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) have demonstrated the advantage of high-order methods for scale-resolving simulation such as large eddy simulation (LES) and direct numerical simulation (DNS). The most popular benchmark from the workshops has been the Taylor-Green (TG) vortex case. I believe the following reasons contributed to its popularity:

Using this case, we are able to assess the relative efficiency of high-order schemes over a 2nd order one with the 3-stage SSP Runge-Kutta algorithm for time integration. The 3rd order FR/CPR scheme turns out to be 55 times faster than the 2nd order scheme to achieve a similar resolution. The results will be presented in the upcoming 2021 AIAA Aviation Forum.

Unfortunately the TG vortex case cannot assess turbulence-wall interactions. To overcome this deficiency, we recommend the well-known Taylor-Couette (TC) flow, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic of the Taylor-Couette flow (r_i/r_o = 1/2)

The problem has a simple geometry and boundary conditions. The Reynolds number (Re) is based on the gap width and the inner wall velocity. When Re is low (~10), the problem has a steady laminar solution, which can be used to verify the order of accuracy for high-order mesh implementations. We choose Re = 4000, at which the flow is turbulent. In addition, we mimic the TG vortex by designing a smooth initial condition, and also employing enstrophy as the resolution indicator. Enstrophy is the integrated vorticity magnitude squared, which has been an excellent resolution indicator for the TG vortex. Through a p-refinement study, we are able to establish the DNS resolution. The DNS data can be used to evaluate the performance of LES methods and tools.

Figure 2. Enstrophy histories in a p-refinement study

Happy 2021!

The year of 2020 will be remembered in history more than the year of 1918, when the last great pandemic hit the globe. As we speak, daily new cases in the US are on the order of 200,000, while the daily death toll oscillates around 3,000. According to many infectious disease experts, the darkest days may still be to come. In the next three months, we all need to do our very best by wearing a mask, practicing social distancing and washing our hands. We are also seeing a glimmer of hope with several recently approved COVID vaccines.

2020 will be remembered more for what Trump tried and is still trying to do, to overturn the results of a fair election. His accusations of wide-spread election fraud were proven wrong in Georgia and Wisconsin through multiple hand recounts. If there was any truth to the accusations, the paper recounts would have uncovered the fraud because computer hackers or software cannot change paper votes.

Trump's dictatorial habits were there for the world to see in the last four years. Given another 4-year term, he might just turn a democracy into a Trump dictatorship. That's precisely why so many voted in the middle of a pandemic. Biden won the popular vote by over 7 million, and won the electoral college in a landslide. Many churchgoers support Trump because they dislike Democrats' stances on abortion, LGBT rights, et al. However, if a Trump dictatorship becomes reality, religious freedom may not exist any more in the US.

Is the darkest day going to be January 6th, 2021, when Trump will make a last-ditch effort to overturn the election results in the Electoral College certification process? Everybody knows it is futile, but it will give Trump another opportunity to extort money from his supporters.

But, the dawn will always come. Biden will be the president on January 20, 2021, and the pandemic will be over, perhaps as soon as 2021.

The future of CFD is, however, as bright as ever. On the front of large eddy simulation (LES), high-order methods and GPU computing are making LES more efficient and affordable. See a recent story from GE.

|

| Figure 1. Various discretization stencils for the red point |

|

| p = 1 |

|

| p = 2 |

|

| p = 3 |

|

|

CL

|

CD

|

|

p = 1

|

2.020

|

0.293

|

|

p = 2

|

2.411

|

0.282

|

|

p = 3

|

2.413

|

0.283

|

|

Experiment

|

2.479

|

0.252

|

Author:

Allie Yuxin Lin

Marketing Writer

In today’s fast-paced and ever-evolving world, staying ahead requires more than just keeping up with the latest trends and technologies. It necessitates continuous learning and skill development, making training an essential component of personal and organizational growth. Whether you’re an individual looking to sharpen your skills or a business aiming to boost productivity, effective training can unlock a wealth of potential. At Convergent Science, we believe constant learning is an indispensable aspect of success that wields the power to transform your career or your company’s future. Our training sessions are where learning feels like an adventure, where every new skill is a boon, and where each attended course is a ticket to revealing your true abilities. In this blog, we will discuss the what, who, when, where, and why of our training program.

At Convergent Science, our training program is designed to get people familiar with our innovative, multi-purpose CFD solver, CONVERGE. Our courses are a way to get acquainted with our software and modeling options while working through a wide variety of example cases. In addition to our introductory training course, which serves as a gateway to CONVERGE, we also offer 10+ different application-focused trainings and 20+ different feature-focused training courses. Many of our sessions also include hands-on practice with our user-friendly GUI, CONVERGE Studio. If you’re looking for a little personalized help, we include a training course specifically so you can work one-on-one with a Convergent Science engineer on a case of your choosing. Additionally, if you don’t see the topic you’re looking for, or if you’d like to organize a training session just for your team, let us know! Our customized training lets you design your own session to best suit your specific needs. In other words, it’s an opportunity for you to tell us your vision of how we can best help you, and we’ll turn it into reality.

“The CONVERGE training I attended significantly enhanced my capability in performing high-fidelity FSI analyses, enabling me to accurately simulate complex phenomena and optimize compressor performance,” remarked Barkın Kılıç, Lead R&D Engineer at Beko. “The training provided invaluable insights into the advanced functionalities of CONVERGE, and the hands-on approach has greatly accelerated my company’s application of these tools in real-world R&D projects. The sessions have also paved the way for us to explore new avenues of research, allowing us to strive toward performance, efficiency, and sustainability targets with a higher degree of confidence.”